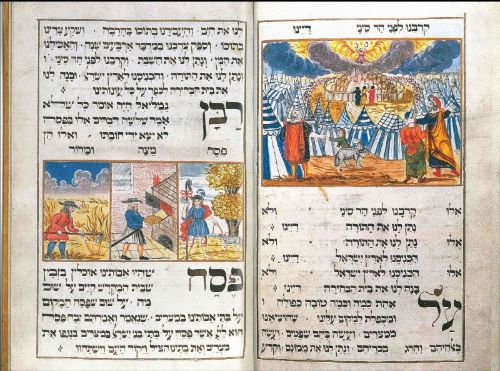

Banner is “Revelation at Mt. Sinai,” Moravian Haggadah, 1737, engraving, facsimile courtesy of Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, Chicago. Found here

In this commentary, I approach Parashat Yitro, Exodus 18:1-20:23, through the lens of disability torah. To define disability torah I refer to a conversation between Dr. Judith Plascow and Rabbi Julia Watts Belser. Dr. Plascow has been writing and speaking about Jewish feminism since the early 1970s and is the author of several works on feminist theology. Rabbi Belser is a rabbi, scholar and spiritual teacher working at the intersections of disability studies and queer feminist Jewish ethics and environmental justice. The two scholars discussed Rabbi Belser’s most recent book Loving Our Own Bones: Disability Wisdom and the Spiritual Subversiveness of Knowing Ourselves Whole.

Rabbi Belser said that she wants to make the case that the Torah which comes through deep interaction with disability experience is not Torah only for disabled folks. As such, Loving Our Own Bones is both a book about reading Torah through disability experience, as well as a book that uses biblical text as a way to illuminate disability experience for everyone and to help us think better about the contours and dynamics and implications of ableism. In this commentary I hope to illuminate disability experience in a reading of Yitro which focuses on the idea of access needs.

In a talk called My Body Doesn’t Oppress Me, Society Does, two disability activists, Patty Berne and Stacey Milbern say that meeting people’s access needs can limit the social, economic, and physical barriers that make physical impairments disabling in an ableist society. When society meets the needs of the community, people with impairments are not necessarily functionally disabled.

Rabbi Belser writes in her book: “The social model argues that people are disabled in large part by specific societal choices; by buildings that lack ramps and elevators; by chairs that are built only for ‘standard-sized’ bodies; by public spaces that assume everyone uses sight to make their way through the world. Rather than trying to press all bodies and minds into a single mold, the social model argues that society needs to provide access and accommodations to those of us who differ from the norm.” (Belser 2023 pg 39).

Consider: every human has access needs. If we build a ramp or an elevator for wheelchair users, that accommodation will also serve parents pushing children in strollers, or a person with a twisted ankle who cannot walk very well this week. If a building is a half flight up from the street, and you identify as able-bodied, will you jump from the sidewalk to the door? No. You will expect a set of stairs. This too is an accommodation and if society did not provide it, you would be functionally disabled. Eyeglasses are another example of an accommodation, without which many people would be functionally disabled. I myself am growing older, with a small hearing loss, diminished eyesight, and creakier limbs. I increasingly rely upon enhanced sound systems, bright light, handrails along the stairs, and a gracious welcome to sit when others stand. Would I call myself disabled? Not yet. Does society disable me right now with echo chambers in social halls, poor lighting, and overly steep stairs? Yes. That is what we mean by the social model of disability.

At the same time, Rabbi Belser cautions us that “disability is both about social barriers and a matter of impairment.” We ought not “overlook the complicated, sometimes painful elements of disability in terms of our bodies and minds.” (Belser 2023 p 250 n 3.)

Now, let’s turn to Parashat Yitro and see how we may read the biblical text through a disability lens as a way to illuminate disability experience, and to better understand the responsibility of society to meet the access needs of all. In this reading, I am not making the claim that our ancestor-scribes set out to teach us about access needs or the social model of disability. But think with me, and those from whom I learn, on the profound wisdom within our text, which when turned and turned, can provide us with deep insights into disability experience.

Section 1: Withering Away and a Place of Shalom

Yitro opens with Jethro, the father-in-law of Moses, joining Moses in the wilderness, where the Israelites have encamped following their escape from Egypt. Jethro witnesses the people standing around Moses from morning to night to obtain justice. This is lo tov, not good, Jethro says. “You will wither up [navol tibbol], as will this people who are with you.. for the thing is too heavy for you to perform alone” (Ex 18:17-18 – translation Aviva Zornberg Moses pg 252). Jethro counsels Moses to gather able, truthful and God fearing men to render the judgements on smaller matters, leaving Moses to expertly judge the heavy matters. If Moses does so, he will endure and the people will come to a place of shalom. (Ex 18:19-23). Note that there importantly are two sides to this: Moses will be supported in his work, and society will be made whole.

Looked at through a disability sensitivity, what might we see here? Without the support of his community, Moses would wither away and become functionally or actually disabled. (per Zornberg Moses pg 252, the verb navol implies erosion of the fibers of his being). With support, not only will Moses thrive, but the entire people will reach a place of shalom, of peace and wholeness. When we meet the access needs of some (Moses), it benefits all. It is doubtful that the ancient scribes set out to give us a lesson in disability justice. But we can see from this text that the ancients valued a model of noticing and supporting a person who is on the edge of withering away. Moses cannot go on serving his people without an extensive network of helpers. For him, these are the stairs that society must build as a matter of course, and Jethro is the architect. Note, and this is important, Jethro does not impose a system upon Moses against his will, but provides wise counsel which Moses takes up.

Section 2: Revelation: All Access

In 2017, while she was still in rabbinical school, Rabbi Lauren Tuchman gave an Eli talk entitled “We Were All At Sinai: The Transformative Power of Inclusive Torah.” Ordained by The Jewish Theological Seminary in 2018, she is, as far as she is aware, the first blind woman in the world to enter the rabbinate. She talks about a very famous midrash, typically mentioned around Shavuot, that says that all Jews, past, present and future were together at Mount Sinai to receive the revelation of Torah collectively. Simultaneous to that, she says, we have a teaching that says that we each received revelation in a way that we could understand it as individuals. The way that we access that revelation is different for each, but each way of access is as valid as any other way of access. She points out that Sinai is an incredibly empowering model.

The Revelation at Sinai begins in Chapter 19 as God tells Moses to convey to the people that God, who has gathered the people to the Divine Presence on eagle’s wings, will make of the people a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. They in return will need to keep God’s covenant. Moses delivers the message and the Children of Israel agree to all that God has spoken through Moses. Next God tells Moses that God will arrive in a thick cloud on the third day, so that people will hear when God speaks to Moses and will trust Moses forever. (Ex 19:3-15).

The third day comes:

Ex 19:16 Now it was on the third day, when it was daybreak:

There were thunder-sounds [kolot], and lightning,

a heavy cloud on the mountain

and an exceedingly strong shofar sound.

And all of the people that were in the camp trembled. (Fox translation via Sefaria)

Note that what Fox translates as thunder-sounds is in Hebrew kolot. In the singular kol means voice. Kolot as a plural translates as thunder (or thunders) when it appears in the Hebrew Bible.

Even at the very beginning of this adventure, we begin with multi-access. We could experience the coming of the divine though hearing, seeing, the feeling of heavy cloud upon the skin, or the reverberations of the shofar though the body. All of the people trembled. No one was left out of the experience. And this is just the beginning! Moses brings the people close to God, right up to the base of the mountain.

Ex 19: 18 Now Mount Sinai emitted-smoke all over,

since YHWH had come down upon it in fire;

its smoke went up like the smoke of a furnace,

and all of the mountain trembled exceedingly.

Ex 19:19 Now the shofar sound was growing exceedingly stronger

—Moshe kept speaking,

and God kept answering him in the sound [of a voice] [vekol]—

Ex 19: 20 and YHWH came down upon Mount Sinai, to the top of the mountain.

YHWH called Moshe to the top of the mountain,

and Moshe went up. (Fox translation via Sefaria)

Here again, amidst the fire, the smoke, the reverberations of the shofar blasting louder and louder, and the extreme trembling or quaking of the mountain, each can perceive this miraculous event though sight, sound, smell, touch, vibration. Some translators, such as modern JPS, take God answering vekol to mean that God answers in thunder. God speaking in 19:19 vekol, ties us back to 19:16 the thunder-sounds of kolot. Whether voice or thunder, God’s communication here is not in words, but, I like to think, powerful enough to experience in the body just like thunder itself.

The final part of this story is when the Ten Commandments are actually delivered. Moses comes down from the mountain and tells all the people the words God has given him to deliver (Ex 20:1-13). The reaction of the attending multitude is very interesting indeed.

Ex 20:15 (a) They see the sounds

Vechol-ha’am ro’im et-hakkolot ve’et-hallappidim ve’et kol hashofar ve’et-hahar ashen

Translations generally concur that the people saw the sound, kolot, which Fox here again translates as “thunder-sounds.” It also could be the plural of voice, and some say “voices.” However thunder much better conveys the overwhelming experience. Again, there is a delightful slipperiness between voice and thunder.

- Fox: Now all of the people were seeing the thunder-sounds [kolot], the flashing-torches [lappidim], the shofar sound, and the mountain emitting-smoke

- Robert Alter: And all the people were seeing the thunder

- Etz Chayim: All the people witnessed the thunder

- Hirsch: And all the people saw the voices

- Zornberg: And the people saw the voices

Ex 20:15 (b) They fall back

vayyar ha’am vayyanu’u vayya’amdu merachok

- “ ‘And the people saw the voices and the lightning and the Shofar blast and the smoking mountain – and the people saw, and they shuddered backwards.’ … What they see and how they see leads them to beg Moses to spare them such a direct revelation.” Zornberg Moses pg 88

- the people “fall back from the mountain. Is this recoil the effect, simply of the rolling thunder and lightning and other sensory impressions? Or is there a moment in which the senses fuse, the moment of ecstasy that mystics have attempted to register, or that the symbolist poets call synesthesia?” Zornberg Exod pg 262-3

From this we may understand that at the great moment of the delivery of the decalogue on Mt. Sinai, when the experience was intense, even mystical and awe-inspiring and fearful, there was a way for every person to take in the experience. As Rabbi Tuchman points out, the way that we access that revelation is different for each, and importantly, each way of access is as valid as any other way of access. What a wonderful celebration of human differences!

There are of course alternative ways of interpreting Sinai. Here are two from which I think we can learn about disability denial.

Commentary

-

- Etz Chayim

- “The Hebrew verbal stem ro’ah (literally, ‘to see’) here encompasses sound. The figurative language serves to indicate the profound awareness among the assembled throng of the overpowering majesty and mystery of God’s self-manifestation. This experience cannot be described adequately by ordinary language applied to the senses.”

- “The text reads literally, ‘they saw the thunder… and the blare of the horn.’ The experience of Revelation was so uniquely intense and overwhelming that the senses overflowed their normal bounds. People felt that they were seeing sounds and hearing visions.”

- THE RASHI CHUMASH BY RABBI SHRAGA SILVERSTEIN via Sefaria

- And all the people saw [(whence we derive that there were no blind ones among them)] [“saw” miraculously] the sounds [emanating from the Mighty One’s mouth], and the lightnings, and the sound of the shofar, and the mountain smoking.

- Etz Chayim

I take exception to the language of Etz Chayim which says that the language of the text is figurative and that people “felt they were seeing sounds and hearing vision.” And with Rashi who says that “seeing the voices” means that miraculously there were no blind people in the crowd.” The commentators wish to suggest that there was no actual opening of multiple senses, no feast for every bodymind. Rashi in particular here is very painful, implying that for the blind to have experienced revelation, they would have needed to be miraculously changed. In a different context, referring to Jacob’s encounter with the angel, Rabbi Belser suggests that a partcular Rashi commentary and associated midrash is “classic disability denial… [which takes] it as self-evident that wholeness is a desirable quality in a hero… they refuse to consider disability as a lasting part of his personhood.” (Belser pg 165.) I would suggest that by denying the ability of blind people to take in the experience, here, too, Rashi is practicing disability denial.

But really, the text says, and the multiple translators agree: they saw the sound – the kolot, the thunder-voices. This is a feast of light and sound, smell and vibration, touch and crossovers between the organs of perception – a moment when each person could be totally engaged in their individual way. I will push this a bit further to suggest that it as if the Holy Presence intentionally goes out of their way to ensure that every single person can receive the divine message, by providing multiple access points to the experience. It is not that the blind are made to see, but that a mode of perception is divinely provided for each and every individual according to their access needs.

I maintain that this is the paradigm, the blueprint, the instruction, for all of us. The Torah tells us that at the moment of delivering the ultimate in divine utterances, the Divine Presence assures that no one is left out. And had Moses not received the help he needed from his community, he may have withered away before bringing the decalogue down from the mountain.

In reading Parashat Yitro as disability Torah, I believe we can learn much about the imperative and the rightness of serving the multiple access needs of our community. Moses needs his army of judges to keep him from withering away and to keep the people b’shalom. And the Divine Presence itself models how we must actively and with lifted hearts provide access and accommodations to all. As Rabbi Belser writes: “The God I know has made a world brimming over with differences, has fashioned minds and limbs that unfold in their own particular ways. The God I know has chosen variation: sometimes minute and almost imperceptible, sometimes bold and brash and beautiful in its rarity and uniqueness.” (Belser pg 64). To repeat Rabbi Tuchman, the revelation at Sinai is an incredibly empowering model. I add, not only is Sinai empowering because of the Torah revealed, but also for the way in which the Torah is revealed to all.

Next time we are in synagogue together to hear the reading of the Ten Commandments, let us not say all stand, but let us say all rise, in body or in spirit.

References

YouTube Video Talks

Belser, Rabbi Julia Watts and Dr. Judith Plascow JWA Book Talk: Judith Plaskow talks with Rabbi Julia Watts Belser about her book, Loving Our Own Bones: Disability Wisdom and the Spiritual Subversiveness of Knowing Ourselves Whole. January 18, 2024. https://youtu.be/8uB_qhY1AXA?si=Fp8utdRBrXgrUExn

Berne, Patty and Stacy Milbern: “My Body Doesn’t Oppress Me, Society Does.” https://youtu.be/7r0MiGWQY2g?si=NYLeifAzfjLv6G2D

Tuchman, Rabbi Lauren. “We Were All At Sinai: The Transformative Power of Inclusive Torah.” ELI Talk Dec 7, 2017 https://youtu.be/WOq77ouo5Og

Books

Alter, Robert. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2004.

Belser, Julia Watts. Loving Our Own Bones: Disability Wisdom and the Spiritual Subversiveness of Knowing Ourselves Whole. Boston: Beacon Press, 2023.

Fox, Everett. The Five Books of Moses: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy. New York: Schocken Books, 1997. (translation also on https://www.sefaria.org/ )

Hirsch, Samson Raphael. The Pentateuch: With a Translation by Samson Raphael Hirsch and Excerpts from the Hirsch Commentary. Edited by Ephraim Oratz. Translated by Gertrude Hirschler. New York: Judaica Press, 1986

Lieber, David L., ed. Etz Hayim: Torah and Commentary. New York: Jewish Publication Society, 2001.

Zornberg, Avivah Gottlieb. Moses: A Human Life. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016. Zornberg Moses

Zornberg, Avivah Gottlieb. The Particulars of Rapture: Reflections on Exodus. New York: Doubleday, 2001. Zornberg Exod