Ruach HaYam teaching presented by Penina Weinberg October 17, 2021

Author Archives: Penina

Hannah Narrative: Thunder, Trouble, and Following Our Inner Voice (August 26 2021)

Ruach HaYam teaching presented by Penina Weinberg August 26, 2021

The Hannah Narrative is recited by Jews every year on the first day of Rosh Hashanah, the New Year (this year falling on September 7). Through a close reading of 1 Samuel 1 we will prepare ourselves to hear the thunder of change and the quiet inner voice of our souls. You will find source sheets here: https://tinyurl.com/RuHay-Hannah Although Hannah is held up as a model of prayer by Jews and Christians alike, how often do we ask what Hannah is actually praying for? What is her heart crying out for? What inner strength does she call on? What external prods and goads does she have? Does Hannah want to be recognized as being more than she appears? Can we as queer folk dig into our transgressive hearts to find a new understanding of Hannah as a woman whose dreams may reach beyond being mother and wife? And what is the role of Hannah’s co-wife, Penninah? Is she a nuisance or a holy troubler of the waters? You may wish to read a commentary I wrote a few years ago. You may enjoy this except from Marcia Falk’s Un’taneh Tokef (page 29 in her book “The Days Between”) A great shofar is sounded And a voice of slender silence is heard. The voice is one’s own a reed in the chorus a breath in the wind Banner is an etching by Marc Chagall (1958): “Hannah Evokes the Eternal.” Hannah in red robe is prominent in the foreground and stretching up to pray. Smaller in background is a figure who appears to be uncomfortable or disdainful. A few livestock are looking on. At 6:45pm ET, meeting will be open for logging in, schmoozing and solving any technical issues. [see below for details] Study begins at 7:15 ET. ——>>>>>> Zoom login can be found in the Ruach HaYam study room https://www.studywithpenina.com/ruach_hayam ——>>>>>> Only recognized names will be admitted to Zoom meeting. Please be sure to RSVP Penina Weinberg is an independent Hebrew bible scholar whose study and teaching focus on the intersection of power, politics and gender in the Hebrew Bible. She has run workshops for Nehirim and Keshet and has been teaching Hebrew bible for 10 years. She has written in Tikkun and HBI blog, and is the leader and founder of Ruach HaYam. *** Ruach HaYam https://www.facebook.com/groups/Ruach.HaYam/ study sessions provide a queer Jewish look at text, and are welcoming to LGBTQ+ and allies, to any learning or faith background, to all bodies, and friendly to beginners***Tzara’at (“leprosy”) and Salvation – Inside and Outside the Gates (June 24 2021)

Ruach HaYam teaching presented by Penina Weinberg June 24, 2021

Ruth and Naomi: The Divine of Human Relationship (May 20 2021)

Ruach HaYam teaching presented by Penina Weinberg

May 20, 2021

Ruach HaYam teaching presented by Penina Weinberg

May 20, 2021

“Beyond the Gates of the City”: Locating G-d’s Social Torah (April 22, 2021)

Ruach HaYam teaching presented by a fabulous guest teacher, Liam Hooper, author of “Trans-Forming Proclamation: A Transgender Theology of Daring Existence”!! April 22, 2021.

Ruach HaYam teaching presented by a fabulous guest teacher, Liam Hooper, author of “Trans-Forming Proclamation: A Transgender Theology of Daring Existence”!! April 22, 2021.

Queerly Meeting Elijah the Prophet (March 18 2021)

Ruach HaYam teaching presented by Penina Weinberg March 18 2021

Ruach HaYam teaching presented by Penina Weinberg March 18 2021

Building Mishkan vs Temple: Willing Heart vs Corvee Labor Feb 28 2021

Ruach HaYam teaching presented by Penina Weinberg February 28 2021

Ruach HaYam teaching presented by Penina Weinberg February 28 2021

The Heart of Judah: The Force of Female Formation Jan 21 2021

Ruach HaYam teaching presented by Penina Weinberg January 21, 2021

Ruach HaYam teaching presented by Penina Weinberg January 21, 2021

The Heart of Judah

From the 14th century “Sister Haggadah” Spain, Catalonia (Barcelona). 1325-1374 CE. Copyright: British Library [Public domain]

WOMEN WHO FORM JUDAH’S HEART

Judah has two formative women in his life who I would argue contribute strongly to the development of a great heart: his mother Leah and his daughter-in-law Tamar.

LEAH

First: Leah. When Jacob, who would be Judah’s father, sets out to take a wife, he choses Rachel, daughter of Laban. (Note, Rachel did not choose Jacob, but that’s a story for another time.) He serves Laban 7 years to be able to marry Rachel. Laban tricks Jacob into taking Leah for a wife before he can marry Rachel. Rachel is from the beginning the favored wife, and Leah pines for Jacob to love her. When her first three sons arrive, Leah gives them names which signify that God has seen her affliction (Re’uven/See, a son!), that God has heard that she is hated (Shim’on/ Hearing) and finally that the third son will join her to her husband (Levi/Joining). (Gen 29:32-34). [Names as translated by Everett Fox]. Taken together, the names show that Leah is unhappily pining away, feeling unloved and alone.

When the fourth son arrives Leah stops giving birth for a time and gives thanks to God. She calls the child Yehuda/Giving Thanks (Gen 29:35 Fox). None of the names are precisely written according to the meaning invested in them. However, biblical names are often assigned a meaning in the text suggested by a word with similar letters. By the explanations of the text, we may see that as she carries and births Judah, Leah is turning her attention away from affliction, hatred, and loneliness, and towards praise for the Divine. Put another way, she stops thinking of herself in relation to how her husband neglects her and connects herself directly to the Divine. I suggest that Judah is born with this connection to the Divine instead of the negative emotions denoted in the names of the first three sons. Furthermore, in the unwritten text we may as a result imagine a special bond between mother and son. This bond based upon thanksgiving gives Judah the possibility of a compassionate heart. We understand already that he may be fated to outshine his older brothers in leadership and in fact be one of the progenitors of King David. This is not to say that Judah is racking up good deeds as he grows up, but, to his credit, he is the brother chiefly responsible for keeping Joseph alive, sold into slavery instead of slain.

TAMAR

The second strong female who molds Judah’s heart is Tamar, his daughter-in-law. Tamar is married in sequence to each of Judah’s older sons, Er and Onan, who die leaving her twice-widowed. Judah packs Tamar off to her father’s house with a vague promise to marry her to the third son, Shelah, when he comes of age. This leaves the widow Tamar chained to Judah’s family, with no chance to find another husband. At that time, a woman without husband and sons would have been in a precarious situation, as she would not inherit from her father. Time drags on, Shelah grows up, and Judah does not make the marriage, perhaps because he fears that Tamar caused the death of his sons. (The text indicates otherwise: that God took both sons for their wickedness). Finally, after the death of Judah’s wife, Tamar waylays Judah when he is in a festive mood, appearing to him as a veiled woman available for sexual encounter. Afterward, Tamar takes Judah’s signet, cord and staff as pledge for payment of a kid from his flock. These articles would have been clearly identifiable as belonging to Judah. When Tamar becomes pregnant, Judah finds out and is furious with her. He threatens to burn her. Tamar produces his signet, cord and staff, proving that he is the father (Gen 38:1-25). At this point, Judah realizes he was wrong to deprive Tamar of her rights and of her societal need to marry Shelah׃

And Judah acknowledged them, and said, She has been more righteous than I; because I did not give her to Shelah my son. And he knew her again no more. (Gen 38:26)

Tamar teaches Judah to recognize a person more righteous than himself. I suggest that this recognition turns Judah himself towards righteousness and enables him to enact love for his father, and to open up Joseph’s heart. Further, that the maternal/divine influence at birth enables Judah to take in the lessons from his daughter-in-law Tamar.

JUDAH AND JOSEPH: THE HEART IN ACTION

The Joseph saga in our text is long and varied. There are two key points which work together to show Judah’s heart in action: Joseph’s withdrawal from his family and Judah’s tender outreach at their meeting.

JOSEPH’S WITHDRAWAL

When Joseph’s brothers sell him into slavery, Joseph prospers in Egypt and becomes the Pharaoh’s right hand man, in charge of his stores. Years go by, yet Joseph never sends word to his family that he is thriving in Egypt, nor does he reach out to them when famine hits. Why doesn’t he do so? Aviva Zornberg suggests that Joseph’s forgetting is a matter of survival for himself after trauma. God makes him forget, but also Joseph embraces the forgetfulness. She expounds on Gen 41:51

“..when he comes to name his first-born son, he calls him Menasseh – forgetfulness: ‘for God has made me forget completely my suffering and the house of my father’ (Gen 41.51). Joseph has forgotten his history, himself… For if he is to survive his own unwitnessed death in the pit, he must forget his father’s house, his past, himself.” Zornberg pg 302.

Joseph becomes unknowable and remains hidden – to himself, to his Egyptian friends and relations, and to his family. He walks like an Egyptian. Then the brothers come to visit and start to penetrate the wall of forgetfulness. All the brothers but one arrive when famine hits in Canaan, Joseph’s homeland. They leave at home Benjamin, the youngest, Joseph’s full brother, the only other child of Jacob’s favorite wife Rachel. Jacob will not hear of Benjamin leaving home, not with Joseph already lost to him.

When the brothers arrive in Egypt, they do not recognize Joseph.

Gen 42:[7] And Joseph saw his brethren, and he knew them, but made himself strange unto them, and spoke roughly with them… [8] And Joseph knew his brethren, but they knew not him.

Joseph knows his brothers but does not reveal himself, in fact he makes himself strange to them. Zornberg suggest this is self-disguise.

“Beyond the asymmetrical drama of recognition and non-recognition, there is the enigma of ‘He made himself strange unto them.’ This reflexive verb suggests a more-than-tactical move of self-disguise on Joseph’s part.” Zornberg pg 303

Joseph accuses his brothers of being spies (mirgalim – the word is repeated 7 times with 25 verses). He demands that they return with their brother Benjamin to prove they are not. In private, Joseph cries when he hears his brothers talk about their guilt in mistreating him and how it has lead to what they think is a requirement to pay for their transgression by bringing Benjamin (Gen 42:21-24). The brothers go home, leaving Shimon behind, bound up, but do not immediately return with Benjamin. Reuben offers to guarantee Benjamin’s safety by pledging that Jacob can slay Reuben’s two sons if Reuben does not return with Benjamin. It’s a ghastly offer and Jacob does not accept (Gen 42:37-38)

When the famine becomes extreme again, Judah steps up to safeguard Benjamin’s return so that the brothers can revisit Egypt. Unlike Reuben, Judah simply takes all the surety on his own shoulders. (Gen 43:8-9). Surely his heart, which has been expanded by the influences of Leah and Tamar, is feeling love for his father. Rabbi Yitz Greenberg writes:

“[F]ar from reacting violently to Jacob’s total possessive love for Rachel’s youngest son, Judah will give up his own life in order not to break his father’s heart again.”

Jacob has no choice but to allow Benjamin to go. When they arrive, Joseph’s heart yearns for Benjamin but he again remains hidden and cries to himself. Joseph’s long years of hiding himself, of “self-disguise,” have crusted over his heart – made it difficult for him to reveal himself even now:

Gen 43 [29] And he lifted up his eyes, and saw Benjamin his brother, his mother’s son, and said: ‘Is this your youngest brother of whom ye spoke unto me?’ And he said: ‘God be gracious unto thee, my son.’ [30] And Joseph made haste; for his heart yearned toward his brother; and he sought where to weep; and he entered into his chamber, and wept there.

Joseph sends the brothers home with bountiful food supplies, and a silver goblet hidden in Benjamin’s pack, then dispatches his steward to accuse them of theft. The brothers swear that whomever has the goblet will be Joseph’s bondsman (Gen 44:9). They find the goblet in Benjamin’s pack and Joseph threatens to keep Benjamin as a servant. This is a disaster! The brothers fall on the ground in front of Joseph as if to plead for Benjamin. Judah is their spokesman. Then a remarkable thing occurs. Judah draws near to Joseph.

JUDAH DRAWS NEAR – CRACKING JOSEPH’S HEART

Then Judah draws near to him [Joseph]. Vayigash elayiv Yehudah. [Gen 44:18].

Why, the rabbis ask, did Judah draw near to the apparent stranger, when he was already in front of him? What can be the meaning hidden behind text that appears to be a repetition of what is already known? The text has already told us that Judah and his brothers have fallen prostrate on the ground in front of Joseph (Gen 44:14).

Menahem Mendel of Vitebsk, (1730-1788) writes:

“The Or ha-Hayyim [Ḥayyim ben Moshe ibn Attar 1696-1743] asks why the term and Judah approached is necessary [since we know Judah was already standing close to Joseph], appropriately explaining that the drawing near to Joseph took place within Judah’s heart, as in the verse ‘As face answers to face in water, so does one man’s heart to another’ (Prov. 27:19). With these words Judah sought to inspire Joseph’s compassion, and therefore he approached him in his heart, drawing near to Joseph and truly loving him, in order to arouse Joseph’s love and spark his compassion. The words of the Or ha-Hayyim are certainly wise and faithful.” Green, pg 153 from Peri Ha-Arets

The Or ha-Hayyim interprets this verse to mean that Judah, in approaching with his heart the unknown Egyptian, who had “made himself strange,” was able to raise up the sparks of love and compassion from Joseph. Judah pleads with Joseph to allow Benjamin to go home and to permit Judah to stay as the bondsman. In response, Joseph opens his heart to all his brothers and reveals his true self. Aviva Zornberg points to the verse where Judah breaks though Joseph’s crusted heart.

This is “the sentence that accesses Joseph’s pain…[Judah says] ‘For how can I go back to my father if the boy is not with me? Let me not be witness to the evil that would befall my father.’ (Gen. 44:34). Zornberg pg 306

Rabbi Yitz Greenberg describes the moment this way:

“Joseph’s blocking wall crumbles. He is flooded with yearning for the father who loved him more than life…. Joseph, moved to the core, reaches out to his father and family. He brings them down to Egypt and nurtures them lovingly through the famine and its aftermath.”

Judah performs the opposite of keeping the stranger at arm’s length. Judah’s compassion for Benjamin, and the loving way in which he approaches Joseph, breaks through Joseph’s Menasseh – his tactical amnesia. We note that Joseph cried upon seeing his brothers, but prior to Judah drawing near, he did not reveal himself. Had he wanted to unite with his family, he could have done that years ago. But Judah drew his heart near to Joseph’s heart and melted the isolation which Joseph had built up around him.

FINAL WORDS

Judah’s heart is steeped in the maternal/divine connection with his mother Leah. It is further tempered by Tamar’s lesson about righteousness. Judah first leads his brothers in saving Joseph’s life, then demonstrates great love for his father. In the end his heart reaches out directly to Joseph’s heart “in order to arouse Joseph’s love and spark his compassion.”

If your neighbor feels like a stranger to you, be like Judah: open your heart and bring the neighbor within arm’s length. Rabbi Julia Watts Belser, who researches ancient texts in conversation with disability studies, queer theory, feminist thought, and environmental ethics, issues a clarion call:

Let us strive together to break down barriers within ourselves and our communities. Let us refashion the crusted architecture of our minds that keeps the Holy at bay.” Belser pg 28-29

SOURCES

Belser, Julia Watts. “God on Wheels: Disability and Jewish Feminist Theology.” Tikkun. 29. 27-29, 2014.

Fox, Everett. The Five Books of Moses: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy. New York: Schocken Books, 1997.

Green, Dr Arthur, Rabbi Ebn Leader, Ariel Evan Mayse, and Rabbi Or N. Rose. Speaking Torah: Spiritual Teachings from around the Maggid’s Table, Vol. 1. 1 edition. Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights, 2013. [Menahem Mendel of Vitebsk, 1730-1788 quoted Peri Ha-Arets] (pg 153)

Greenberg, Rabbi Yitz “Can We Save the Unity of the Jewish People? Parashat VaYigash 5781” Accessed 12/27/20: https://www.hadar.org/torah-resource/can-we-save-unity-jewish-people#source-9535

Zornberg, Avivah Gottlieb. The Murmuring Deep: Reflections on the Biblical Unconscious. New York: Schocken Books, 2009.

Brief story of Judith

In the Septuagint (LLX), Judith is a bad-ass heroine, heartily accepted and lauded by her people after she saves them from Holofernes. She is portrayed as quite independent – relying upon her faith in God, but very inner directed, brave, and splendid. Lots of intertextual links to Jewish heroes, male and female. Jerome’s Latin Vulgate (4th C CE) turns her into a chaste super pious widow who is basically following God’s direction – still a heroine, story much the same, but more directed – not so much agency – and not so fully respected. A story you would expect from a celibate Christian priest.

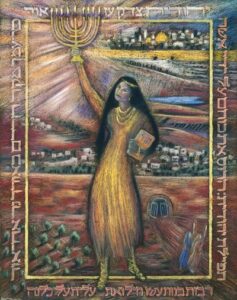

There is zero in Jewish tradition concerning Judith until about 1000 CE. Never was a Hebrew version of the LLX story. Jerome, in making the Latin Vulgate claims to have translated from Hebrew but this cannot be established. None of the Jewish historians, philosophers or rabbis mention her until she appears in the middle ages. Her story then is similar to LLX, but gets wrapped into multiple midrashic and liturgical stories of Hanukkah and Judah. She becomes quite prominent as a Jewish heroine (see first illustration – above), perhaps partly because it is a time of increasing nationalism (12th-14th centuries or so), perhaps in reaction to Christian adoration of the Virgin Mary. Judith remains a hero to the Jewish people over time (see second illustration).

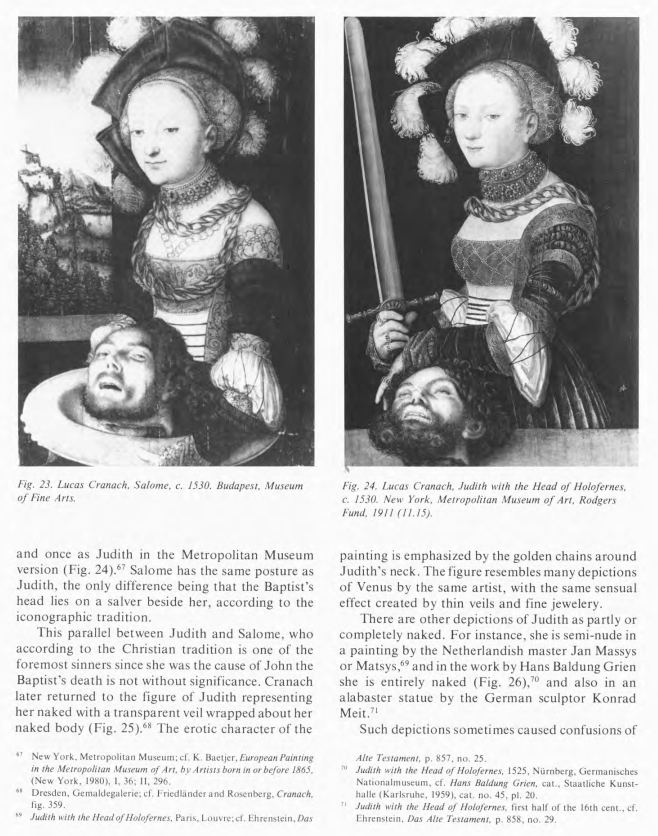

Christian art in the 15th century mixed Judith up with quite misogynist views of women. The art in last frame shows that she was conflated with Salome and both were portrayed as rather vile seducers.